We were in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan at Morimoto Restaurant, and we were inside the bubble.

We were in the Meatpacking District of Manhattan at Morimoto Restaurant, and we were inside the bubble.“Beautiful people,” as Jack Donaghy explained in a recent episode of 30 Rock, “are treated differently than moderately pleasant looking people. They live in a bubble. A bubble filled with kindness and free drinks.”

My friends and I have always felt that we should be treated as if we were inside the bubble. To my knowledge, though, none of us believes that we actually have the looks to access this magic globule – with the possible exception of Dave, who once spent an entire double-decker bus tour of London admiring his own reflection in the windows of the buildings we passed. Overall, though, we think that we get only what we deserve.

But at Morimoto, you feel that you have access to the very best of everything, and that you can get away with anything. You are surrounded by wealthy, beautiful people, and by the power of suggestion, you begin to believe that you, too, are one of the City’s modelesque big hitters. The wait staff fawns over you like a mother looking after the needs of a sick child. And when you go to the bathroom and step into the stall, an automated toilet lid rises to greet you. People outside the bubble don’t get this kind of treatment.

Not only were we seemingly in the bubble, but it was Saturday night and we hadn’t seen each other for a while. In celebration, we were drinking straight Vodka as we waited for the food to come. Dave said he had started watching Top Chef and thought he was ready to join Colicchio’s team of judges. This led to a loud argument over whether Dave knew enough about food to be on national television. Even though the conversation reached an inappropriate volume, no one gave us nasty looks. Maybe it was that the tables have plenty of space between them. Maybe it was that the noise is reduced by translucent partitions and wavy white sheets of canvas and fiberglass on the ceiling and along the walls. Or, just maybe, we were inside the bubble.

The food came, and first up was the lamb carpaccio. My last experience with raw meat was in D.C. at the Ethiopian restaurant Etete, where they served kitfo as a thick mound of beef lumped at the center of the injera. Morimoto’s carpaccio was a welcome contrast: light, silky slices of lamb, presented simply with green onions, grated ginger, and olive oil.

The braised black cod with a ginger-soy reduction and the sea bass in sweet sake kasu were unremarkable, but the sashimi received unanimous praise from our group. Terrine-like cubes made from layers of hamachi, smoked salmon, barbecued eel and seared toro were luscious and hugely flavorful.

The braised black cod with a ginger-soy reduction and the sea bass in sweet sake kasu were unremarkable, but the sashimi received unanimous praise from our group. Terrine-like cubes made from layers of hamachi, smoked salmon, barbecued eel and seared toro were luscious and hugely flavorful.Then, Ed, red-faced and mouth full of sea bass, pointed and yelled: “Morimoto!”

I was pessimistic and debated whether it was worth turning around. Ed was on his fifth or sixth glass of vodka. On the other hand, Morimoto is pretty recognizeable. Maybe it was some other Japanese guy sporting all-black clothes, goatee, pony-tail, and black-rimmed glasses?

Reluctantly, I turned, and sure enough, Masaharu Morimoto was relaxing in the back of the dining room, drinking a beer with the hostess.

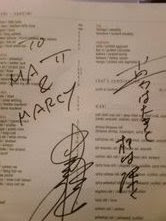

Seconds later, menu and pen were in hand as I made my way to the legendary Iron Chef, who boasts 16 wins on the program. Despite my inebriation and my experience with getting autographs from Top Chefs, I was nervous. This guy makes Bravo's show look like Slop Chef.

I noted that Morimoto was drinking a Rogue Ale – his specialty line of beers. I also noticed that the hostess was doing most of the talking; Morimoto is known for having a soft-spoken manner and heavy accent. The guy came to Manhattan in 1985, so I’m not sure why after 24 years he still hasn’t found time to learn English. His speaking is so bad that during the judgment phase of Iron Chef his voice is usually dubbed or subtitled.

Distracted from her monologue, the hostess rolled her eyes when I tapped Morimoto on the shoulder, but the chef didn’t seem to mind the adulation. He might have had a few too many Rogue Ales, though, because he missed the front of the menu, accidentally signing the back. He nodded cordially when I thanked him, but he didn’t say a word.

I returned victoriously to our table. We regarded our satisfied stomachs and Iron Chef memorabilia with a sense of accomplishment. Life inside the bubble was good: we had clearly been treated with kindness.

Then the bill came. Our eyes widened in terror, and the pop was almost audible. No free drinks or discounts of any other kind. It’s a good thing we didn’t get the certified “saga” Japanese beef. That runs $30 per ounce.

As Liz Lemon’s good-looking boyfriend said when she stopped letting him win at tennis, I don’t like it outside the bubble.